Distributing a new medical device widely – and quickly – is both an economic imperative… and a headache. Access to the highly regulated market, excessively complex procedures, and health professionals who are not easy to convince to adopt a new device. Focus on the main levers that can be used to optimize this adoption.

Seeing your new product or service massively – and rapidly – adopted by your customers: this is the dream of all marketers, whatever the market or sector. And for good reason: the diffusion of their innovations is a crucial issue for all companies. The speed and breadth of this dissemination are key factors for commercial success. Moreover, it is what determines whether a new product can move from the niche market stage to the mass market stage…

Of course, achieving optimal diffusion for your new products is far from being a piece of cake. And the process depends on many factors. First and foremost is the diversity of the population targeted by the innovation. A distinction is made between ‘diffusion’ within a group of people and ‘adoption’ at the individual level. Adoption is defined as “the [individual] process that details the series of steps taken between the discovery of a product and its final adoption”.

Adoption of medical devices: a strong and complex issue

While the adoption of new products is a challenge in any sector, it is even more challenging in the medical device market. There are at least two reasons for this:

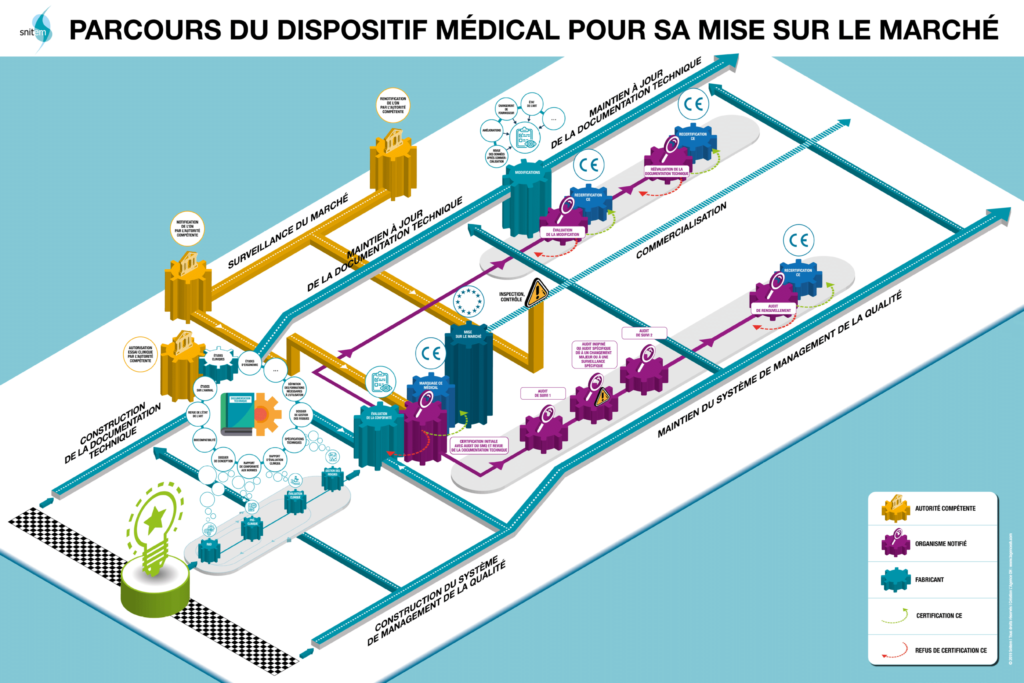

- Market access for medical device manufacturers is a long and complicated process. Stringent regulatory requirements, prior clinical evaluations, integration of reimbursement mechanisms, etc. are all part of the process. The development and launch of new medical devices is a journey fraught with obstacles, sometimes of different kinds depending on the country targeted. The visual below (source SNITEM) illustrates this path for the French market, which is reputed to be one of the least accessible. A survey carried out by the interministerial center for forecasting and anticipating economic change (Pipame) places France among ‘the last European countries in which the marketing of a medical device would be envisaged’. Even though steps are being taken to make the medical device market more accessible, it is understood that it is of paramount importance to achieve rapid uptake of new products once they are launched on the market… Because the window of opportunity is narrow: “The technology and market cycle of a medical device is 2 to 5 years. This is one of the shortest life cycles in the health industry (that of drugs is 10 to 12 years),” says Snitem. Moreover, companies in the sector are not mistaken: in a prospective study by PIPAME (based on a survey of manufacturers), they place “facilitating the adoption and dissemination of the offer” as the very first criterion for creating value, ahead of “a response to a proven medical and patient need”.

- Medical devices, as diverse as they are, have one thing in common: they are “user-dependent”: their implementation, efficacy, and outcomes are linked to the act of a health professional or, more broadly, any user (up to and including patients themselves in some cases). This considerably complicates the model of device adoption in the face of

- The diversity of users involved (expectations, constraints, skills, etc.),

- The performance and benefits of medical devices which depend on their “good” implementation by users,

- Potential organisational or procedural changes induced by the use of a new medical device.

This user-dependent nature generates adoption issues even before a new device is on the market when the benefits it is supposed to bring are assessed. “The importance of learning-by-doing has long been recognised by research and has been documented for the use of many devices […], says Snitem. For a medical device to demonstrate significant benefits, it must be used under optimal conditions. These conditions include the training of teams and the learning curve of health professionals.

The model for the diffusion of technological innovations

Once on the market, how does a new medical device spread? Among the abundant literature on the question of the diffusion of innovation, the work of Everett Rogers – initiated in the 1960s and whose latest version dates from 1995 – is still a reference in many sectors, including the most technological. The model defended by this American sociologist and statistician describes “the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels, over time, among the members of a social system”. According to him, adoption at the individual level breaks down into 5 phases:

- Knowledge: when exposed to innovation, the individual reacts according to his profile and the social system in which he evolves;

- Persuasion: the crucial stage where the individual takes a position on the innovation and reacts according to the characteristics of the new product;

- Decision-making, where the individual engages in use and evaluation, enabling him or her to adopt or reject the innovation;

- Implementation, where the individual seeks assistance to reduce uncertainty;

- Confirmation: the individual seeks information to confirm their choice.

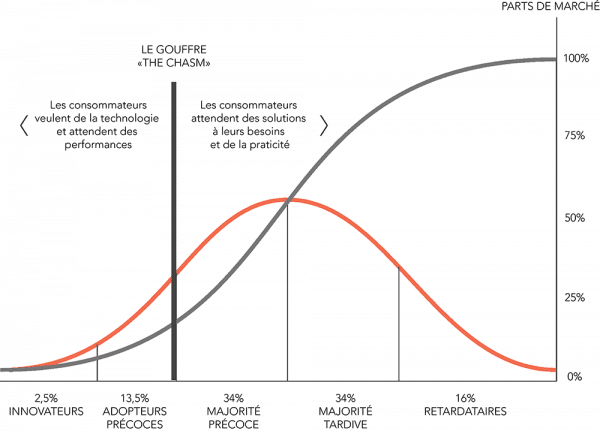

From this model, Rogers deduced two curves (see below):

Source: http://www.actinnovation.com/innobox/diffusion-innovation

- The adoption curve or “bell curve”, represents the five user profiles that an innovation must convince to spread widely: the innovators (2.5%), the early adopters (13.5%), the early majority (34%), the late majority (34%) and the latecomers (16%). It should be noted that these profiles, with their very different expectations, correspond to a purely statistical distribution that is independent of the characteristics of the population observed.

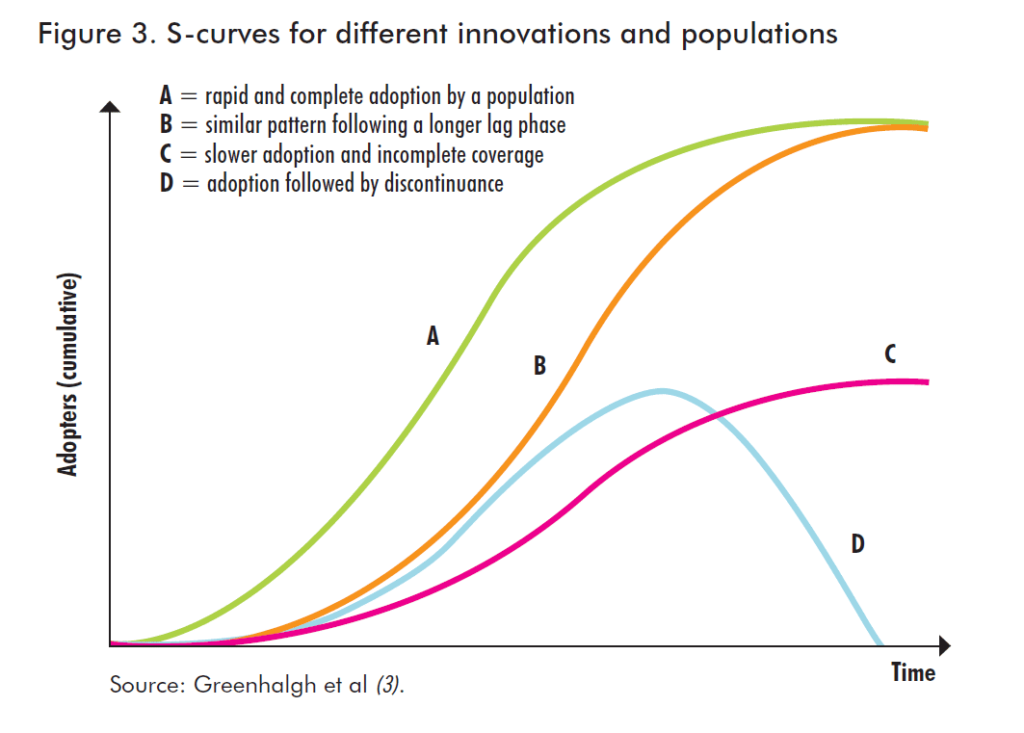

- The S-curve represents the evolution of the diffusion of an innovation. This is the cumulative distribution of adopters over time. This is a generic curve, which will vary according to each innovation and each user population, as illustrated by the graph below (source: Greenhalgh et al – Barriers to innovation in the field of medical devices – World Health Organisation).

Levers for the adoption of new products

In his model, Everett Rogers identifies 5 intrinsic characteristics of innovation that influence the speed of its diffusion and explain “between 49 and 87%” of the variation in the adoption of a new product:

- Relative advantage, as it may be perceived by the user/consumer, both economically and socially.

- Compatibility, i.e. the level of fit between the existing values and practices of potential users and those needed to use the innovation.

- Complexity: an innovation that requires learning will a priori be slower to spread.

- The possibility of testing may facilitate adoption by reducing uncertainty and encouraging word of mouth.

- The observability of results. This factor makes it easier to demonstrate the benefits of the innovation and thus reduce uncertainties.

Other exogenous factors (or externalities) are also cited as potential facilitators of innovation diffusion. These are referred to as network externalities, particularly in the technology and information technology industries:

- Direct externalities: a “large” number of users of a product or service can increase its value.

- Indirect externalities: the existence of a (large) number of complementary goods to the new product increases its value (e.g. video games for a games console).

Medical devices: a less linear adoption pattern

Although this model of innovation diffusion is a reference and already provides keys to improve/accelerate adoption, it is often considered too simplistic for the medical device sector: “Although this model has the merit, in particular, of conceptualising opinion formation within peer groups, its linearity does not account for the complexity of the contextualised feedback mechanisms that influence technological developments in medicine,” reads Barriers to innovation in the field of medical devices, a companion document to the report of the WHO Priority Medical Devices Project. Demonstrating that scientific evidence alone is not sufficient to ensure the successful diffusion of new medical devices, the report concludes that there is an interaction between technological and social systems, engaging multiple actors towards an inter-organisational interface/structure. In the end, the diffusion of medical devices may result from stable organisations and processes, but may also be dependent on unexpected events… This makes it a process that is neither totally random nor predictable”.

Without being totally discarded, Everett’s linear model is thus modified, enriched, or challenged by multiple studies specific to the medical device market (notably those of Fitzgerald, Consoli, Blume, Greenhalgh, or Gelinjs & Rosenberg), which highlight several specificities, including:

- The fact that in the world of health care, a single solution is rarely unanimously accepted by professionals,

- Innovation in medical devices is often incremental and involves much more complex exchanges (feedback, corrections, etc.)

- Innovation does not only involve health professionals but many other stakeholders (consultants, universities, companies, regulators, etc.)

- The idea that interpersonal influence via networks, opinion leaders, etc. is the dominant mechanism of diffusion, and that this model of adoption develops within quite different social structures: “Doctors thus operate with informal and horizontal networks, conducive to the diffusion of influence between peers. Nurses, on the other hand, have more formal and vertical networks, better suited to cascading information and the transmission of authoritative decisions”.

- Innovative medical devices can lead to profound organisational changes, generating their problems: obstacles to change, transfer of responsibilities, training needs, etc.

“The translation of knowledge into practice can be understood as a long-term learning process, characterised by a constant exchange of information between the developers of the technology and its users to progressively reduce the uncertainties associated with the implementation of a new treatment,” concludes the WHO study.

Facilitating the discovery and use of medical devices: one of the keys to success Whatever dissemination model is deemed to be the most appropriate for medical devices (the family of medical devices is sufficiently large that they do not all obey the same rules), one factor systematically appears to be an essential lever… or an obstacle to dissemination if it is not sufficiently taken into account: information and training in the use of medical devices.

This is true in all countries, developed or developing, according to the WHO, which cites among the “common” barriers to innovation “lack of training of personnel in the use of new devices, hostility to established medical practices and reluctance to admit a need to improve skills”.

In a report by the Conseil Général de l’Économie (General Economic Council) dated February 2019 and presenting strategic reflections on industrial policy in the field of medical devices, this need for training also figures prominently: the report recommends developing initial and continuing training on medical devices. The report recommends developing initial and continuing training in medical devices and “designing and implementing training plans for health professionals, support structures and manufacturers to meet real needs, which are both scientific and technological and also organisational and experiential”.

Now that this lever for improving the dissemination of medical devices has been identified, it remains to determine the most effective means of training users of this equipment, optimising the learning curve, and limiting the risks of errors or poor handling… A problem identified in the CGE report: “the key is to identify the needs in this field and to develop appropriate training programmes. Few training courses manage to integrate all the needs, which are both scientific and technological but also organisational and experiential”.

New technologies, such as virtual reality and immersive video, provide very interesting new solutions to these problems…