Often depicted holding a needle,inthe public imagination nurses are”the ones who pokeus.” In this sense, placing peripheral venous access is a procedure representative of the profession, although of course there is much more to it than that. With 25 million peripheral venous catheters placed every year in France, it is also a procedure that nearly every nurse will encounter.

Definition and Indications

This is an invasive procedure that involves the insertion of a short catheter into a peripheral vein. An alternative to oral access, it can be used for:

- administering medications

- supportive fluids / electrolytes

- transfusing labile blood products

- temporary parenteral nutrition, up to 10 days (e.g. pending a CVC)

- injecting contrast agent during an exam.

Regardless of the indication, the value of PVA should be reassessed on a daily basis (SF2H 2019).

Catheter: To each its own (color)!

The short catheter is a tubular medical device made of polyurethane or fluorinated polymers with a maximum length of 80 mm, in accordance with European standard NF EN ISO 10555 5.

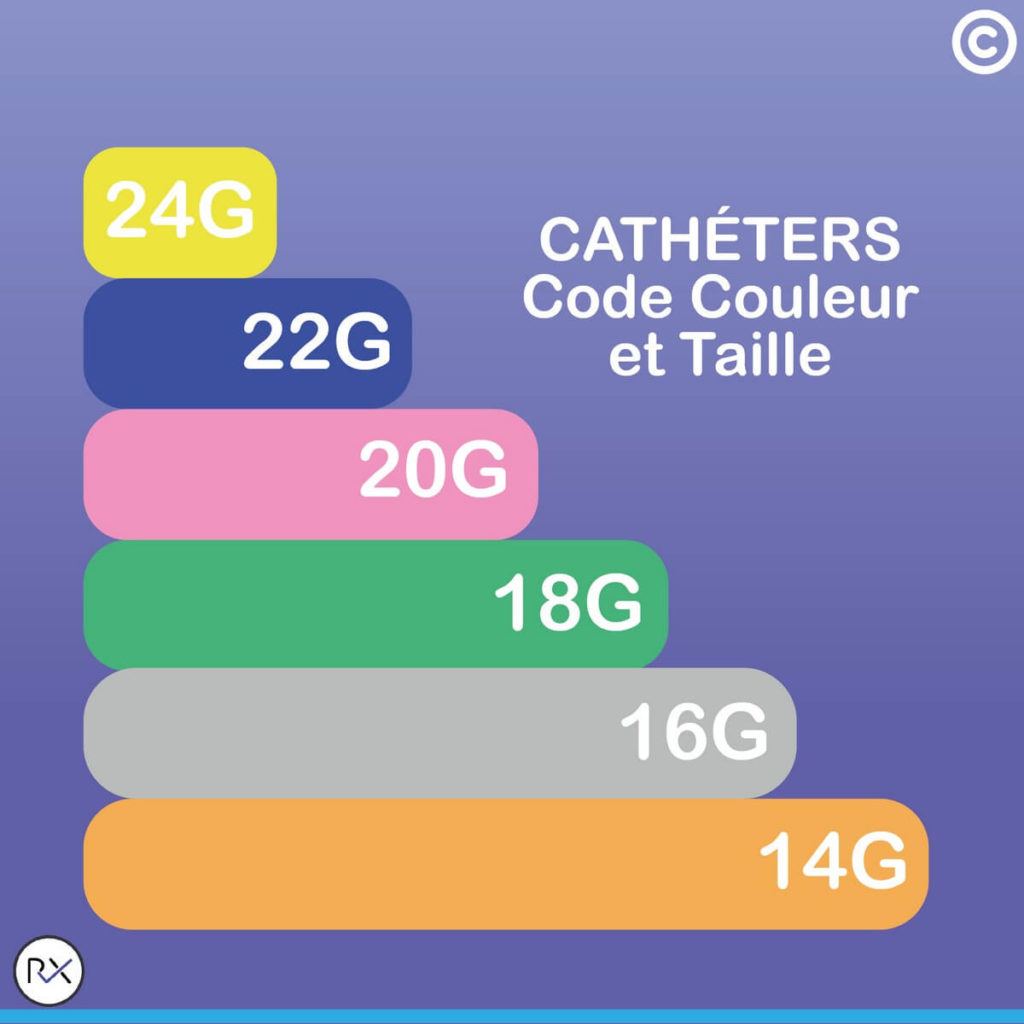

Its caliber, or diameter, expressed in Gauge (G), is represented by a color code that follows an international standard.

- Yellow 24G, 22 mL/minute max.

- Blue 22G, 36 mL/minute max.

- Pink 20G, 65 mL/minute max.

- Green 18G, 103 mL/minute max.

- Grey 16G, 196 mL/minute max.

- Orange 14G, 343 mL/minute max.

The catheter is chosen based on the indication for the PVA and the caliber of the patient’s vein.

Legal Framework

Catheter placement and removal falls under the prescribed role of nurses according to Article R4311-7 of the French Public Health Code (Decree No. 2004-802 of July 29, 2004). It should be noted that even ifthe external jugular vein is superficial, nurses are authorized to place a PVA only in veins located in the limbs and on the skull (epicranial veins in children).

Catheter monitoring is part of a nurse’s role according to PHC Article R4311-5.However, this procedure is not restricted to specialized nurses. With a medical prescription, midwives (PHC Article L4151-3) and medical electroradiology technicians (PHC Article R4351-2) are also authorized to perform it.

From theory to practice: a convoluted path

It all began with the discovery of blood circulation, described by the English physician William Harvey in 1628. Less than 30 years later, the British scientist Sir Christopher Wren performed the first “infusion”on a dog, using a goose feather and a pig’s bladder. He was experimenting with “a pathway for introducing fluids into the bloodstream.” And intravenous injection was born!

However, a variety of complications began to appear. As early as 1667, the Italian physician Francesco Redi observed that animals died when a vein was opened, allowing air to enter. The mechanism of gas (or air) embolism was demonstrated in 1839. In 1778, Dr. Regnaudot described “that in general, injections initially result in shivering, a rise in temperature.” Air embolism, infection, thrombosis, venous injury, and extra-venous infusion all resulted in the procedure being abandoned. Injections and transfusions were even banned by the Paris Parliament in 1670, which considered them too dangerous.

Asepsis –with hand washing in 1846 (Dr. Semmelweiss) and instrument sterilization in 1877 (Pasteur) –was essential for controlling the risk of infection and thus reducing deaths.

During the 20th century, techniques and equipment evolved to further ensure patient safety. Needle-based devices were made increasinglysafe during the 1990s and 2000s, with the goal of preventing accidental exposure to blood (AEB) for caregivers.

Training

For the nursing student in France, peripheral venous line placement is part of teaching unit UE4.4 S2 (Therapeutics and contribution to medical diagnosis). This procedure requires linking technical concepts with the rules of ergonomics, organization and principles of asepsis. Students learn progressively more as care becomes more complex. The procedure involves monitoring and removing short catheters as well as placing them. This Ifsi (French nurse training institute) teaching module also incorporatespreparing therapeutics, managing infusion lines, and blood transfusions, all related to this procedure.

Practical work and occasionally even simulation assist in training, so that nurses are not performing this technique for the first time on a live patient.

This commonprocedure is not without risk. History has shown us that many complications are possible, and infections are still common even today. It is the nurse’s role to monitor the insertion site. Standardized assessment tools are available, such as the Maddox scale or the Insertion Point Monitoring Scale, to monitor, anticipate and thus prevent risk.

Although moderntechniquesand equipment are safer and more effective than ever before, good practices must be followed to use them properly.